On the Trail

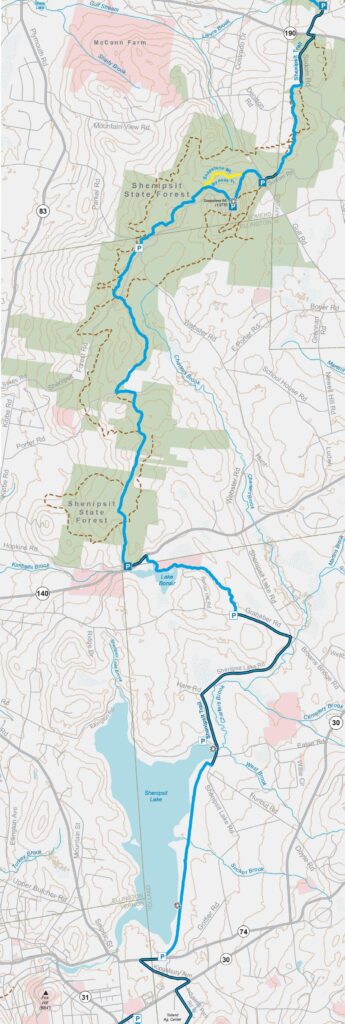

The Shenipsit Trail: From Grahaber Road in Tolland to Gulf Road in Somers

By Joe Neafsey

My wife, PJ, and I first started hiking after we met in college in 1971. Although I grew up in southwestern Connecticut, I had never heard of CFPA or the Blue-Blazed Hiking Trails. When we moved back here in 1976, I remember seeing a blue oval on Route 42 on my way to work. Curious, I stopped on my way home one day and found a small parking lot and kiosk describing the route of the Quinnipiac Trail. I wrote down the address of CFPA (at the time, in East Hartford), became a member, and soon received the 1976 Bicentennial Edition of the Walk Book in the mail. Over the next few years, we hiked along the Quinnipiac, Laurel, Lone Pine, Metacomet, Mattatuck, Naugatuck, Sleeping Giant, Regicides, Westwoods, McLean Game Refuge, and other trails. When we moved to West Stafford, we discovered that the Shenipsit Trail was about five minutes from our house. Within a few months, we hiked the entire 50-mile trail, from the Massachusetts line to East Hampton, Conn.

At a CFPA event in 2017, I happened to sit next to Harry and Weezie Perrine, who manage a northern section of the Shenipsit Trail. I told them I was retired and lived close to the trail, and within minutes, I was recruited to be a trail manager. The northern section of the Shenipsit Trail starts at Grahaber Road in Tolland and runs north through the Shenipsit State Forest to Old Springfield Road in Stafford. My section ends at the state forest entrance on Gulf Road in Somers.

Find the complete map in the Connecticut Walk Book, published by CFPA and Wesleyan University Press.

Edgar L. Heermance once said, “A good trailsman always leaves a trail a little better than he finds it.” Although his wording could use some updating, this sentiment summarizes my desire to give back to the trails that have given so much to me and my family over the last 46 years. I’m also grateful to Hugh Owen who generously shares his ideas, time, and labor to help clear blowdowns, trim brush, clean drainageways, and place steppingstones across muddy sections of the trail.

“Shenipsit” is a Mohegan word that means “at the great pool,” likely a reference to Shenipsit Lake. The trail follows foot paths, cart paths, tote roads, and haul roads through the woods. From the 16th through the early 20th centuries, these forests were major charcoal production areas used to make iron. Today you can still see many charcoal mounds along the trail, especially along the yellow and blue by-pass trail. Look for subtle undulations—roughly 30 feet in diameter— of black soil rather than brown. Colliers who tended these mounds lived in nearby shelters called hovels. A little probing can often yield small charcoal fragments.

Also, the enduring work of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) can be seen along the roads and picnic areas in the Shenipsit State Forest. Connecticut’s CCC Museum, located in the state forest at the former Camp Conner, is an interesting side trip. The museum, the second largest CCC museum in the country, contains more than 900 photos, displays, and other artifacts from the state’s 21 camps, which operated from 1933 to 1942.

The highlight of this section is the tower at the summit of Soapstone Mountain, the highest point along the trail. After a steep climb, the tower provides sweeping views of the Connecticut River Valley to the west. You can also visit an old soapstone quarry near the summit.

Rock formations and outcrops are found throughout this section. While on the trail, notice the layers or “foliations” in the rock, evidence of its marine sediment origins. This can easily be seen in the outcrop the trail climbs just north of the Parker Road crossing.

The entire trail, from Great Hill Pond in East Hampton to Old Springfield Road in Stafford, runs parallel to the Eastern Border Fault on 450-million-year-old bedrock. The Glastonbury gneiss was formed from a volcanic arc when the small continent of Avalonia collided with North America, closing the 3000-mile-wide Iapetus Ocean, uplifting the crust, and forming the once-Himalayan scale Appalachian Mountains.

East of this fault lies a fracture from which lava erupted to form one of the thickest flows in the world. Soapstone Mountain is thought to have been one of the magma roots of these ancient volcanos. The fault was displaced about three miles vertically and is now filled with sediments eroded from the once-30,000-foot mountains to the east. Since this area was a tropical region at that time, the sedimentary rocks in the Connecticut River Valley are red-colored. Today’s Shenipsit Trail would have been about five or six miles under these mountains at the time.

Gradually, these mountains eroded down almost to sea level, but constant regional uplift (like a melting iceberg) and differential erosion, where red sandstone rocks erode faster than hard metamorphic rocks, created the Connecticut River Valley and the Eastern and Western Highlands we see today. Much later, about 15,000 years ago, glaciers scored this landscape, leaving behind rounded hilltops, gravel deposits, and erratic boulders.

I find the contrast between the simple act of hiking this trail and the complex geology of what lies beneath my feet fascinating. I’m humbled by the thought that the closing of a 3000-mile-wide ancient ocean and continents colliding created a volcanic chain, and that its metamorphosed lava remnants are now the gneiss domes over which the trail traverses. To me, this illustrates how short a time we human beings have existed on this Earth. Beats thinking about how many more blowdowns or snow downs we need to clear!

I also like to think that I’m taking care of this trail for the generations to come.

Joe Neafsey is a retired USDA NRCS Water Quality Specialist. He is a proud father and grandfather. Besides travel, he likes landscaping his yard and garden, hiking, biking, and kayaking.

Learn more about the Shenipsit Trail