The Slower You Go, the More You See

As she hikes the New England Trail, artist Emma Aiken notices the little things that most people miss.

By Hanna Holcomb

As she hikes sections of the 235-mile New England Trail, Artist-in-Residence Emma Aiken is zooming in on the details that many hikers miss.

“I’m always drawn to the small stuff,” she said. “It’s just so cool to look up close. It’s like a whole little world.”

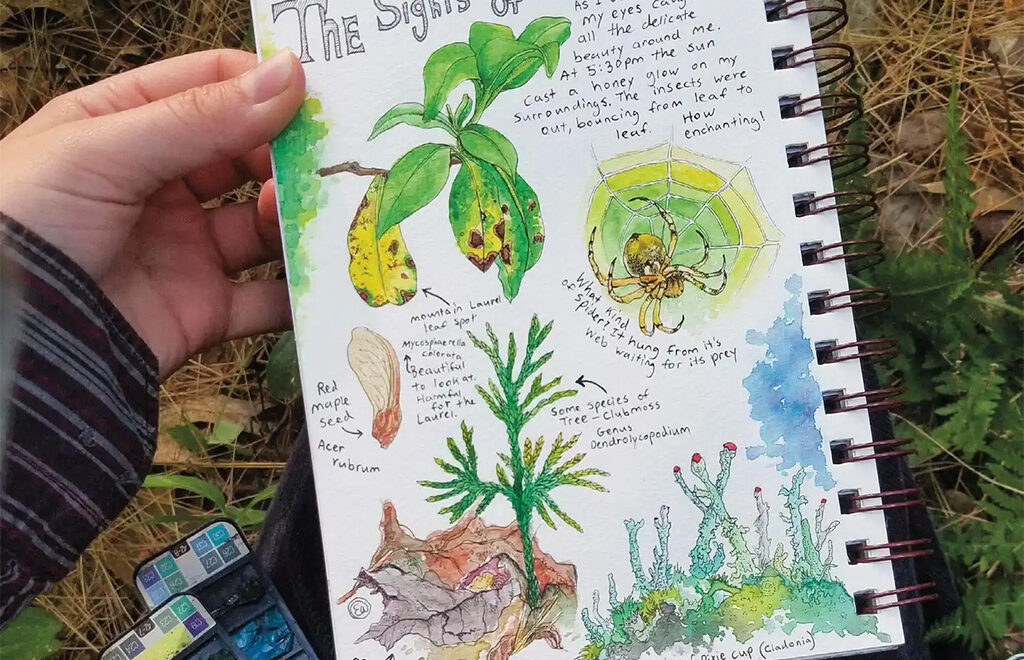

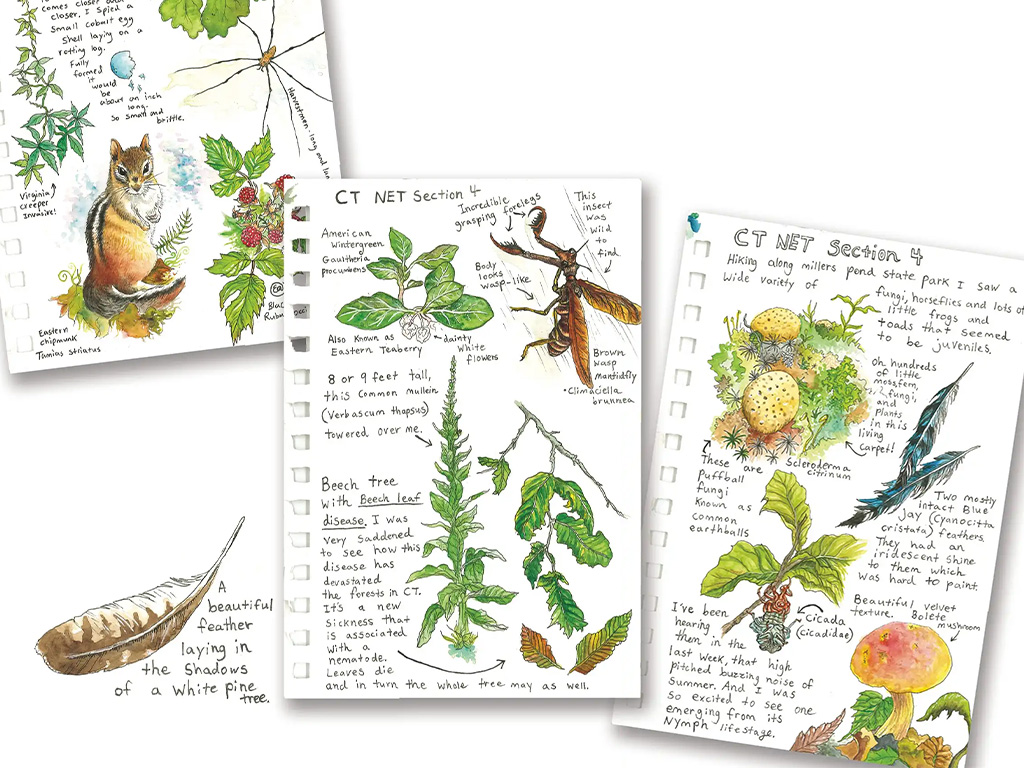

From berries to ferns and frogs, Aiken shares wonders from the trail through nature journaling, the process of documenting experiences in nature through art and writing. Her intricate watercolor and pen drawings, along with her words, connect viewers with the sights and feelings of a particular section of trail. Aiken’s artistic expertise is highlighted in her work, but she emphasizes that nature journaling is for everyone. It helps us to become immersed in nature, she says, in turn sharpening our observation skills and sparking curiosity.

Aiken grew up in Belchertown, Mass., where she developed a love for art and science at a young age. She was homeschooled for much of her childhood and able to pursue her interests more deeply than traditional schooling might have allowed. Her mom, a former teacher, was especially good at turning her curiosity into meaningful lessons. Her dad, a science teacher, instilled in her a love of science. They explored outside together, looking under rocks and using field guides to identify what they discovered. Later, she studied biology and liberal arts at Holyoke Community College where she was particularly interested in zoology and ecology-related courses.

“Creativity and science go hand in hand.”

She didn’t study art in college, but art has always been a big part of her life. Inspired by her mother’s creativity, she took a handful of art classes and began to specialize in detailed nature art and in fantasy drawings.

“My fantasy drawings are always a little nature-inspired,” she said. “I do a lot of dragons and morphs of different creatures. It’s very free flowing, whatever comes to my mind I draw.”

Aiken’s first introduction to nature journaling was as a teenager during a semester school program in Wisconsin.

“We did ‘sit spots,’ which is when you sit at and return to a specific spot throughout a certain period of time,” she said. “We’d go every week and record the new things that happened. That was my first experience with nature journaling, and that was definitely inspiring.”

Now 22, Aiken is combining her passion for art, science, and nature as the New England National Scenic Trail (NET) Artist-in-Residence.

The Artist-in-Residence program, which began in 2012, is one of more than 50 artist residency programs hosted by the National Park Service. Through the program, artists use the surrounding landscape as inspiration for their craft, whether it be art, poetry, or music. Recent recipients include Marisa Williamson, a multimedia artist who created public art projects exploring whose stories on the trail are memorialized and whose are forgotten; and Ben Cosgrove, a composer who wrote and performed music inspired by the trail.

As this summer’s Artist-in-Residence, Aiken is hitting the trail with a watercolor kit, pens, pencil, and paper. With no set destination in mind, she hikes slowly, looking for things that catch her eye. “I’m actually trying to go really slow because the slower you go the more you see,” she said.

She sketches what she sees and writes about what she’s hearing, seeing, and feeling in the field. “I’ll just be walking around and be like, ‘Oh, that’s a cool piece of moss,’ or ‘Woah, that’s a really interesting mushroom,’” she said. “Whatever really piqued my interest is what I’ll draw.” She creates as much as she can while on the trail, but if weather and biting insects force her to keep moving, she later uses guidebooks and photographs to help finish the entries.

Aiken says that nature journaling helps her observe nature on a deeper level. She’ll sometimes spend an hour drawing one thing, a fern leaf, for example, to capture its intricate details accurately. During the 1800s and early 1900s, many scientists, such as Charles Darwin, did the same. Without highpowered cameras, researchers relied on art and text to record their observations and share their discoveries with others.

“Often people are focused on getting to the top of the mountain. But there are so many different points where you can stop, sit down, and just enjoy it.”

Even with today’s advanced imaging tools, art is still a great way to increase our understanding of science. By drawing an observation, rather than writing about it or taking a photo, we are more likely to notice details that we would have otherwise missed. Drawing requires deep focus and is an active way to visually and physically engage with an object. Through drawing, our brains create strong connections between what we’re observing and our existing knowledge and experiences. These connections help us form stronger memories and can lead us to wonder more about what we’re observing.

“I think that creativity and science go hand in hand,” said Aiken. “Science is all about asking questions and being curious and following your interests, and that’s really the same with art.”

By slowing down and observing, art helps us develop a stronger connection with nature, resulting in a greater appreciation for and responsibility to the environment. The resulting artwork can also inspire environmental stewardship. For example, the artwork of Thomas Moran, created from a journal he kept during an 1871 expedition to the Yellowstone region, helped convince Congress to establish Yellowstone as the nation’s first national park.

Everyone can benefit from it, but nature journaling can be particularly effective in classrooms. Studies have shown that sketching and annotating observations of natural phenomena improve students’ critical thinking, attention to detail, and the ability to organize and categorize information. In addition to positive learning outcomes, nature journaling gets kids outside, connecting them with local ecosystems and helping to lower feelings of stress.

Part of Aiken’s goal for this residency is to inspire others to create.

“Something I always say is that I want to create a creative ricochet,” she said. “I’m hoping that through my work and workshops people get inspired and then pass that along to someone else. It just ricochets to others.”

To help people get started in nature journaling, Aiken is hosting two workshops to teach people how to nature journal. She’s also created a zine, a small circulation of self-published work, as a how-to guide for nature journaling. This zine, in addition to one she created about insects on the trail, can be found at libraries, trailheads and visitor centers along the trail. In addition, her work will be displayed in a gallery at the Holyoke Children’s Museum in October.

Aiken’s advice for new nature journalers is to simply go out and do it.

“Don’t be scared, just go out,” she said. “You can tailor it to any of your skills. Like if you love writing or poetry you can focus on that. If you love sketching or you want to get better at sketching, just go sit and try to draw with no pressure.”

She also recommends keeping it to yourself. That way you can capture your observations, thoughts, and experiences without the pressure of other people’s judgment.

With just a pencil and paper and something in nature that interests you, whether it’s a summit view or a plant growing in the sidewalk, you can start a nature journal.

“It’s a great way to slow down,” said Aiken. “It’s a great way to get off your phone and just observe and be immersed in nature. It’s so mind clearing.”

Hanna Holcomb, a native of Woodstock, Conn., is a freelance writer and naturalist living in Idaho.