Coexisting with Coyotes

Despite attempts to eradicate the species, one of North America’s most misunderstood, coyotes are thriving in Connecticut.

By Hanna Holcomb * Photo by Jaymi Heimbuch

Whether you live among forests and farm fields or high-rises and highways, you are likely neig bors with the eastern coyote (Canis latrans var.). These adaptable predators survive and thrive in Connecticut’s rural, suburban, and even urban environments. “They’re in every town in the state,” said Jason Hawley, a wildlife biologist at the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP). “There’s really no limitation to where they can be.”

Whether you live among forests and farm fields or high-rises and highways, you are likely neig bors with the eastern coyote (Canis latrans var.). These adaptable predators survive and thrive in Connecticut’s rural, suburban, and even urban environments. “They’re in every town in the state,” said Jason Hawley, a wildlife biologist at the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP). “There’s really no limitation to where they can be.”

Over the past 200 years, few animals have been trapped, hunted, poisoned, and hated with as much intensity as the coyote. Despite attempts to eradicate the species, coyotes have managed to increase both their range and abundance. Today they’re present from Alaska to Panama and have made themselves at home in our major cities.

“They’re here to stay,” Hawley said. “We have to learn to live with them in Connecticut since they’re certainly not going anywhere.”

Coyotes have a long history of living near humans. Prior to 1900, they lived in the western two-thirds of the U.S., from Canada to the Yucatan Peninsula. They feature prominently in the stories and mythology of North America’s indigenous peoples. Though depictions vary, coyotes often appear as trickster characters, both good and evil, witty and foolish.

“A lot of people say the reason coyotes are here is because we destroyed so much of their habitat, and sometimes that is true. But it also seems that coyotes are kind of choosing to be somewhat close to people.”

Dana Goin, wildlife outreach specialist, Wolf Conservation Center

European colonists, however, viewed coyotes and other predators, such as wolves and mountain lions, as menaces that threatened livestock and hunting stock like deer and elk. Private landowners, as well as state and federal agencies trapped, shot, and poisoned predators with zeal well into the 20th century. In 1931, for example, the federal Animal Damage Control Act appropriated $10 million for coyote eradication. While other large predators became “extirpated” or “locally extinct” due to extermination efforts, coyotes responded by increasing their numbers and seeking new territories.

“They got here in spite of our best efforts to literally eradicate the entire species,” said Chris Nagy, cofounder of the Gotham Coyote Project, which studies New York City’s coyote population and Director of Research and Education at Mianus River Gorge.

Aided by the removal of larger predators, a more open landscape, and their own wit, coyotes began moving east in the early 1900s. To reach New England, they traveled north and crossed paths with dwindling populations of gray wolves in the Great Lakes. Wolves and coyotes are physically able to mate and produce viable offspring, but often avoid doing so. Wolf populations were so low, however, that they reproduced with coyotes out of desperation. As coyotes kept moving east, they also mated with feral dogs and the eastern or Algonquin wolf.

The eastern coyote’s unique genetics has earned them nicknames like “coywolf” and “coydog.” Percentages vary, but one study by Stonybrook University of 462 eastern coyotes revealed a genetic profile of 64% coyote, 13% gray wolf, 13% eastern wolf, and 10% domestic dog. Today, with ample populations for finding mates, there is no evidence of significant interbreeding between coyotes, wolves, and dogs in the United States.

Coyotes are helping to fill the role of top predator left vacant when wolves were extirpated from the eastern United States. As omnivores that prey on small mammals and occasionally fawns, coyotes may help keep deer and rodent populations in check. They also eat berries and vegetation. Their adaptability to varied diets and habitats has enabled them to thrive in a variety of environments.

“A lot of people say the reason coyotes are here is because we destroyed so much of their habitat, and sometimes that is true,” said Dana Goin, wildlife outreach specialist at the Wolf Conservation Center in South Salem, N.Y. “But it also seems that coyotes are kind of choosing to be somewhat close to people.”

Though many people perceive urban areas as lacking natural resources, for coyotes they are teeming with opportunity. “Where there are people, there are inevitably rodents,” said Goin. “There are often a lot of crops or gardens which is going to attract rabbits, and there are lots of squirrels and chipmunks, so there’s going to be a lot of food.”

Studies have shown that urban coyotes maintain smaller territories than rural coyotes, in part because cities can have a higher abundance of resources. In addition, their territory is often defined by the boundaries of the city park or green space that they claim.

Scat analyses have shown that coyotes don’t rely on anthropogenic food sources as much as one might expect. A study of more than 1400 coyote scat samples by the Chicago-based Urban Coyote Project found that their diets primarily consisted of natural prey species like small rodents, white-tailed deer, and eastern cottontails as well as fruit and birds. Human-associated food items were found only at the most-developed sites and made up just 2% to 25% of their diet.

Tips for Coexisting with Coyotes

- Never intentionally feed coyotes and remove other attractants like pet food, garbage, and bird feed

- Keep pets under your supervision— keep cats indoors, particularly at night, and dogs on a leash

- Close off crawl spaces under decks and buildings to prevent coyotes from denning there

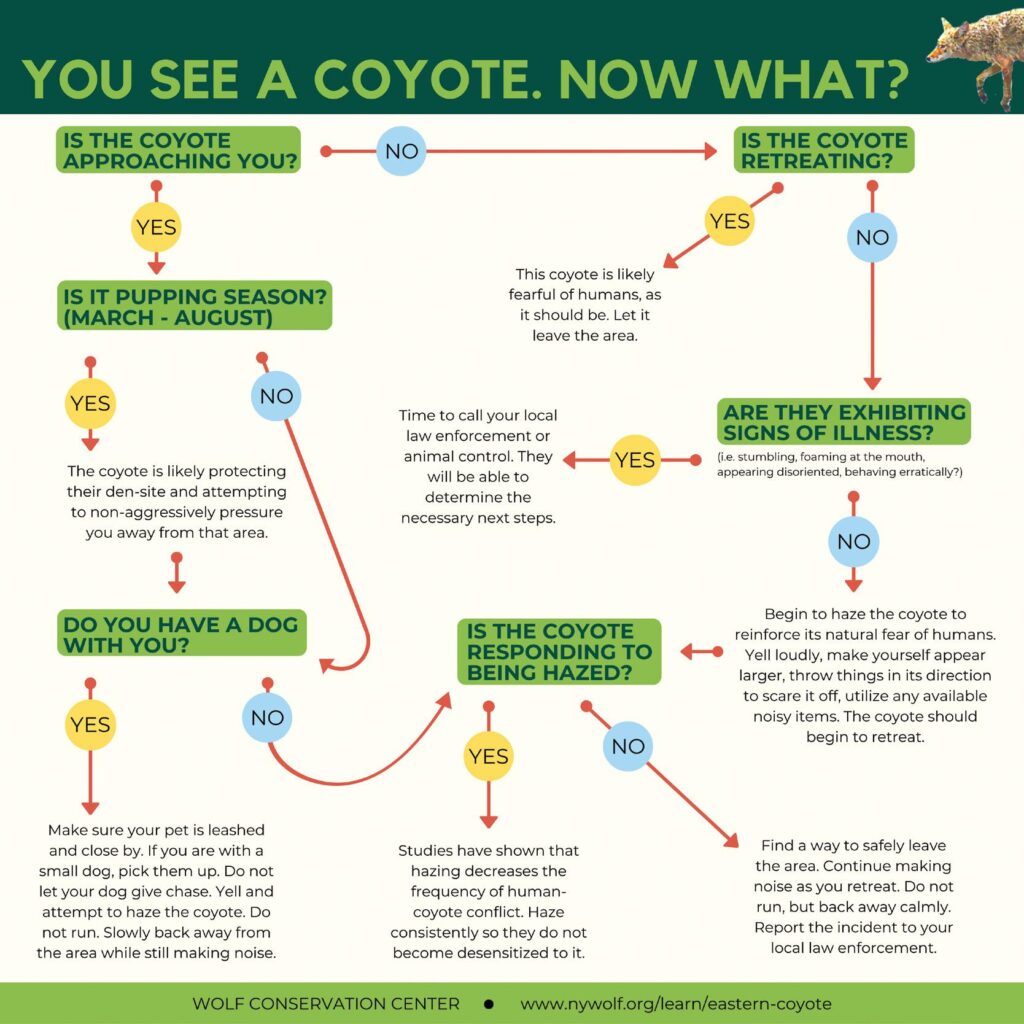

- Attempt to scare away coyotes by yelling or using an airhorn

- Report abnormal or unusually bold behavior to the DEEP Wildlife Division and your local Animal Control Officer

A DNA analysis of coyote scat in NYC by the Gotham Coyote Project found that roughly 60% of samples contained at least one human food item, like bananas. Nonetheless, their diet primarily consisted of mammals like raccoons, rabbits, voles, and deer as well as birds, insects, and plants.

Nagy started monitoring New York City’s coyotes in 2011 by placing camera traps in green spaces in the Bronx. In subsequent years, he watched as coyotes began to colonize more green spaces and other parts of the city.

“You see a leapfrog progression year to year, and it happened pretty fast across the Bronx,” said Nagy. “Most of the green spaces with some amount of forest in them now have coyotes.”

Colonizing new green spaces, however, is no small feat. Coyotes live in family units and the two parents, who mate for life, defend a territory where they raise their pups. Typically, pups are born in mid-March to early April. By October to December, some pups strike out to find their own territory and mate, while others stick around with mom and dad to help raise the next litter. Without a map to guide them, the coyotes that leave have to contend with highways, waterbodies, and other hazards in hopes of stumbling upon suitable habitat. “It’s risky for these animals to leave the place they were born,” said Nagy. “And they sort of have to do it if they want to reproduce.”

“They’re here to stay. We have to learn to live with them in Connecticut since they’re certainly not going anywhere.”

Josh Hawley, wildlife biologist, CT DEEP

Despite living in close proximity to people, coyotes still work to avoid us. For the most part, they are crepuscular, meaning they are most active at dawn and dusk. However, in urban areas, coyotes are more nocturnal to avoid interacting with people.

Sam Lewis is a wildlife biologist who uses game cameras to study eastern coyotes at the McLean Game Refuge in Granby, Conn. She found that on the eastern half of the refuge, which has more trails and is closer to Granby’s town center, coyotes frequently use the trail system, but almost always at night.

Camera traps are an indispensable tool for conservationists. When an animal crosses an infrared sensor, it triggers a digital camera to take a photo or video. This eastern coyote was photographed by a camera trap at the McLean Game Refuge. Photo courtesy of Sam Lewis.

“They’re still relatively skittish around people,” said Lewis. “For the most part when we’re hiking in the woods, we’re maybe talking, or we’re stomping, or we have a pet with us that’s making noise, so they generally will hear us before we even notice them and try to get away.”

While coyotes want to avoid us, urban coyotes have to be more tolerant to human presence than their rural counterparts. “If you go out in the wilderness with a coyote or fox (and) get within 50 yards or 100 yards, they’re just going to run away. That’s it’s comfort zone,” said Nagy. “But if that was the case for animals in New York City then they would just be running away 24/7. There’s always a person.”

Coyotes, he explained, have to become habituated to human presence and sounds, such as lawn mowers and vehicles. The problem, however, is when they become conditioned.

Conditioned coyotes have likely been fed by people and start to seek out interactions and food rewards. They may exhibit bolder behavior which can lead to bites and attacks. According to data from DEEP, there were 69 coyote “conflicts” in 2021. Conflicts vary in severity, however, from people simply being upset that there are coyotes in their yard to aggressive behavior towards pets and people. Since April 2022, DEEP has issued three permits to Nuisance Wildlife Control Operators to remove problem coyotes. Such permits are only issued when coyotes are directly causing problems, often attacking dogs.

In addition, Connecticut allows coyote hunting year-round and trapping for about five months of the year, both without bag limits. Nationwide, about half a million coyotes are killed every year as a means to remove “problem” animals and “control the population.” Ironically, indiscriminate coyote removal can lead to a larger population.

“Coyotes are density dependent breeders,” said Lewis. “When there’s a mated pair that defends a territory and one or both of the coyotes are killed, the other ones in the area are just going to breed more now that there’s more territory and more resources for them and their kin.”

Preventing conflicts and understanding why conflicts occur, rather than simply removing coyotes, can promote better coexistence. Goin offers a program through the Wolf Conservation Center to create “Coyote Wise” communities. The program teaches local officials and residents about coyote behavior and ecology and how to prevent conflicts. The goal is to help people feel safer while recreating outdoors, and to promote coexistence. “I love talking about coyotes, but I also love knowing that we’re making people more comfortable and making coyotes a little bit safer as well,” said Goin.

Southbury is currently the only Coyote Wise community in Connecticut. Animal Control Officer Melody Sandquist said offering Coyote Wise programming has helped residents become more comfortable living with coyotes.

“People have come up to me and said, ‘I understand more about coyotes now and I don’t have to be petrified,’” explained Sandquist. “I definitely think the programs have been successful in mitigating some of that fear that people have.”

Though coyote conflicts are rare, they often increase during the breeding and pup rearing season, from January to mid-summer, especially when a hiker or walker has a dog. “The coyote sort of views the dog as just another coyote that’s infringing on their territory and is a potential threat to their family groups, particularly their pups,” said Hawley.

Rather than being scared off when a hiker is on the trail, coyotes may be more likely to stand their ground, or even follow people to get them away from a den site, which can be frightening. “What they do sometimes is called “escorting.” If they have a den nearby, especially if they have pups, and you’re walking near it, they might follow you to make sure that you’re getting away,” said Lewis. The best thing to do is turn around, go the way you came, and avoid the denning area until about July.

Conflicts can occur when residents intentionally or unintentionally leave out food rewards like garbage and dog food. Bird feeders can attract coyotes to residential areas as well. “They don’t necessarily eat the seed, but they are attracted to the small rodents and mammals that may be under the feeder,” said Colburn. Removing these attractants can reduce the amount of time coyotes spend near people.

Coyotes do also occasionally attack and kill small pets like small unleased dogs and cats but keeping these animals inside or leashed helps protect them. Residents can also help reinforce coyotes’ natural fear of people through hazing. Making loud noises by yelling, banging pots and pans, or using an air horn can scare them off.

“Hazing them reinforces that people are unpredictable, loud, and kind of frightening, because that’s what they normally think,” said Goin. “But sometimes they unlearn that fear if we’re not giving them reason to believe it.”

Coyotes are perhaps the most adaptable animal in the world, able to exploit nearly any habitat, from farm field to city park. Though they live comfortably among people, we are less comfortable with them. Misconceptions and fears often obscure their true nature as a resilient, shy, and opportunistic predator. But people and coyotes can safely coexist. With a few simple changes, we can adapt to the coyotes’ presence, just as they’ve adapted to ours.

Hanna Holcomb, a native of Woodstock, Conn., is a freelance writer and naturalist living in Idaho.

Read Jaymi Heimbuch's Interview